Cutting Trees in Tenryu Forest in Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan

Lumberjack Activity Report #1

Located in the central region of Honshu, Japan in Hamamatsu City, Shizuoka Prefecture, Tenryu Ward is a major forestry area, with about 90% of its area covered in forest, 80% of which are artificial forest. Known as one of Japan’s three great artificial forests, the “Tenryu Beautiful Forest” boasts a history of 500 years.

This time, we visited Tsuyoshi Maeda, who works in forestry here in Tenryu and is actively involved in afforestation projects. Together, we set out to cut down a 60-year-old cedar tree.

Into “Kicoro Forest”

On November 6, 2020, 13 participants, mostly junior employees, headed to “Kicoro Forest,” the base of operations for Maeda-san, a professional lumberjack in Tenryu.

This forest, though primarily composed of cedar and cypress plantations, is home to broadleaf trees such as zelkova, camphor, and oak. Once a dark, neglected artificial forest, it has been carefully restored by Maeda-san over five years. Today, the forest floor is lush with charming ferns like Conteri Kuramago-ke, and the area has transformed into a bright, healthy woodland.

After struggling up increasingly steep slopes, we reached the base of a cedar tree about 60 years old. On this day, instead of using the chainsaws typically employed by lumberjacks, we would cut it down with hand saws.

Determining the Felling Direction

Before cutting down a tree, the first step is to decide the direction in which it will fall. The simplest method is to fell the tree in the direction of its natural center of gravity—typically downhill on a slope. However, this approach carries the risk of the tree collapsing prematurely and causing greater damage upon impact. To ensure safety and minimize damage, we chose to use a rope and guide the tree to fall uphill instead.

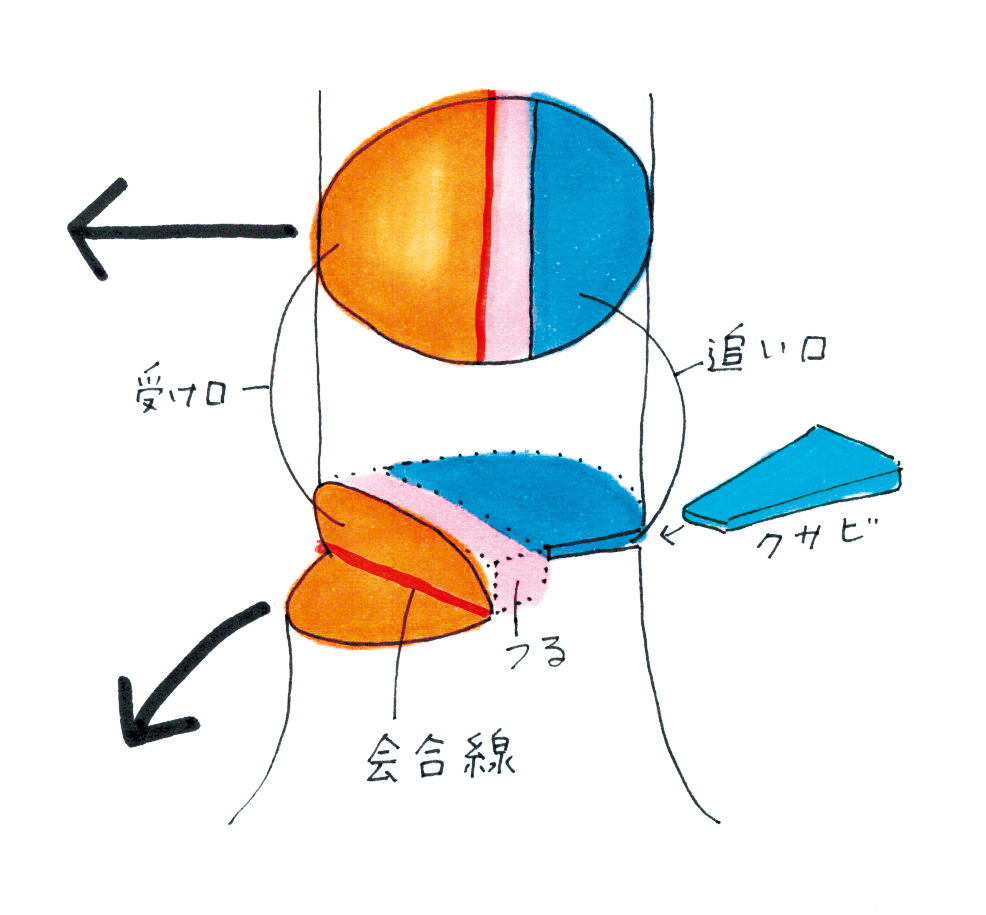

Creating the Undercut and Backcut

Once obstacles and escape routes have been checked and the felling direction determined, it’s time to start cutting. First, we make the undercut by sawing from two angles—straight across and diagonally downward. This notch largely determines the felling direction, accounting for about 80% of the outcome.

Next, from the opposite side, we make the back cut by sawing horizontally. The remaining strip of wood, called the “hinge,” acts as a pivot and allows for final adjustments to the felling direction. This step requires careful checks and precise work to ensure safety and accuracy.

Pulling Down the Tree

While waiting for our turn with the saw, we practiced tying a rope as high as possible on the tree. Following Maeda-san’s advice: “Don’t use force; send waves through the tree”, participants quickly improved. It turns out that both sawing and pulling require technique, not strength.

The pulling team climbed the slope and drove wedges into the back cut. At the signal, “Ready—go!” everyone began pulling the rope. “Let go once it starts to fall!” Maeda-san called out as he added a final cut with the chainsaw. With a cracking sound, the tree leaned, its leaves rustling loudly as it slowly came down. From the first notch to the final fall, it took about an hour to bring down a single tree.

The Weight and Life of a Tree

When we touched the freshly cut surface of the cedar, it was surprisingly wet—water seeped out as if the tree were still alive. The 1-meter log we cut as a souvenir was so heavy that lifting it was a challenge.

“This log weighs about 60 kilograms,” explained Maeda san. “Most of that weight is water drawn up from the roots.”

Maeda san hopes to use the life of these thinned trees to help create new forests. As we carried the log away, we also carried a new understanding of the task ahead.

[Today’s Teacher] Tsuyoshi Maeda, Lumberjack/Representative of Kicoro

Since moving to Tenryu in 2003, Maeda san has dedicated himself to forestry. He also works to share the beauty and importance of forests through activities like FUJIMOCK FES, where participants experience everything from cutting trees to crafting wood items. In addition, he gives lectures at schools to inspire the next generation.

NCM Roundtable: After Our First Tree-Cutting Experience

Seven participants from Nikken Sekkei Construction Management, Inc. (NCM) shared their thoughts online.

Tanaka: The forest air felt so refreshing. We’ve all been working remotely and hardly had a chance to go outside (during COVID-19), so it was great to meet people again and move our bodies. Since I was first to cut, I felt nervous thinking that my cut would determine the angle of the notch for everyone else. The moment I started sawing, the wonderful scent of the wood surprised me.

Hayakawa: Unlike processed lumber, fresh wood is full of moisture and feels softer. Pulling the saw felt heavy somehow. It had been a long time since I used a saw, and honestly, it was just difficult.

Yoshimoto: Indeed. Although I had an idea of how to cut from the preliminary lecture, it didn’t go as planned when I actually tried it. The saw cuts better when pulling, so I ended up cutting only the near side, which changed the felling direction. Those who came later had a hard time cutting the far side.

Yoshioka: The back cut was harder than the undercut. As we got closer to the center of the tree, it became more difficult to cut, and we became more cautious, fearing it might fall. In the end, Maeda san did a lot of the cutting.

Sagimori: Practicing with the rope was also interesting. I was nervous when everyone was watching me tie the rope during the actual cut. It was tough because the tree didn’t fall despite pulling hard.

Shimura: When the tree fell, it didn’t snap suddenly. Maybe because of the fibers or the moisture, it felt like it was slowly tearing apart as it went down

Hayakawa: After the tree fell, touching the cut surface left my hand quite wet. I realized that trees, like flowers, absorb water to live.

Anamizu: I was surprised by the amount of water in the tree, but even more impressed by the strength of its fibers. A tree with a 40 cm diameter can stand on its own—that’s amazing.

Yoshioka: I often buy lumber at home improvement stores, but when I saw the cut surface, I realized how little sapwood there actually is. To grow knot-free sapwood for a 105 mm square pillar like those used in houses—how many years would that take?

Tanaka: I’ve participated in tree planting on Mt. Fuji before, so I thought trees just needed to be planted and would grow on their own. This time, I learned that without human care, forests won’t become healthy. Maeda san’s idea of ‘designing the forest’ really left an impression.

Hayakawa: I hope we can share the importance of maintaining forests and find ways to harness the forest’s vitality.

Thoughts and Beyond

Relay column by NCM employees Participating in the Lumberjack Activities

I joined the “Lumberjack Activity” as one of the junior employees, curious to learn how everyday wooden products are made. I had never even held a saw before, but small curiosity led me here.

I realized there’s a big difference between knowing and actually doing. This hands-on experience taught me the value of facing challenges sincerely, one step at a time.

Unmanaged artificial forests have their reasons. While this small effort cannot solve all the complex issues, I believe that small actions can connect and grow into a movement beyond one single company—and maybe, just maybe, change the future a little.

Would you like to join us and experience cutting down a tree for yourself?

Shoko Tanaka

Nikken Sekkei Construction Management (NCM)

Cutting Trees in Tenryu Forest in Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan 掲載号